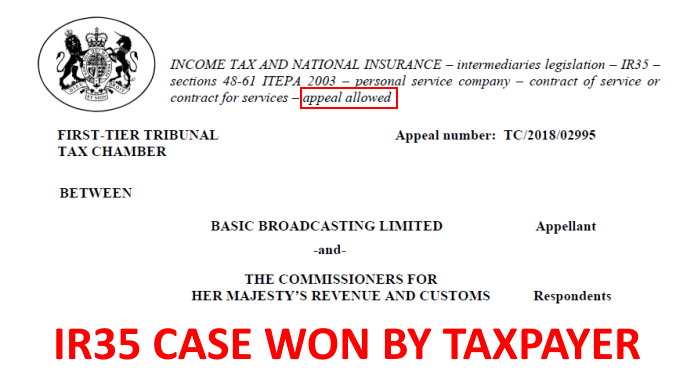

After more than seven years and two tribunal hearings, an IR35 case ruling has finally been made for the broadcaster and writer Adrian Chiles and his media-based company Basic Broadcasting Ltd (“BBL”). Judge Cannan has ruled in his favour, allowing the appeal relating to services provided to the BBC and ITV between the five tax years spanning 2012 to 2017.

The tribunal's partial analysis found that all the contracts created the initial impression of contracts of employment. But once they had crucially finished considering all the circumstances and activities as a whole, they decided that all engagements should be treated as being entered into as part and parcel of the nature and extent of his business. On that basis, they concluded they were contracts for services and not contracts of employment, and therefore IR35 did not apply.

Dave Chaplin, CEO of IR35 Shield, who attended the tribunal and has spoken to Mr Chiles, said: "Mr Chiles has been subject to more than seven years of hell with this investigation in a manner no-one should have to endure. The judgment unequivocally shows that HMRC was entirely wrong in its assessment and failed to consider all the circumstances. He is the victim of a very poorly run investigation by HMRC inspectors.”

Chaplin further adds that, "The tribunal also made it clear that 'there is no suggestion Mr Chiles set out to avoid tax by supplying his services through BBL '.”

The detailed decision documented the plethora of evidence that fully supported their conclusions, and it appears there are no credible legal avenues for HMRC to appeal. Chaplin says: “Given what Mr Chiles has been put through, including the considerable unrecoverable costs of having to fund two hearings, it would be in my view, an abuse of power, if HMRC decided to pursue him further."

Covid caused delay and a costly rehearing

The first hearing took place in November 2019, a full five years since the beginning of HMRC’s investigation. The average wait for a judgement at the time was a year but, as Judge Cannan explained, the Covid-19 situation made matters worse for Chiles: "The hearing of this appeal offers an unfortunate illustration of some of the awful effects of the pandemic."

Judge Barbara Mosedale initially heard the appeal in November 2019, but she contracted Covid-19 in the early part of the pandemic and suffered from long covid. She could not return to judicial work or write the decision despite several attempts. The tribunal subsequently decided that the appeal would be partially reheard, which led to two more days of oral submissions, a full two years later, in November 2021.

Chaplin says: "The wait for a decision post-hearing is a period where the appellant is on tenterhooks. Before the pandemic, most media cases took around a year to reach a decision. Instead, Chiles had to wait two years and then face yet more costs with the rehearing."

Upon learning of the planned rehearing from Chiles, ContractorCalculator sent a Freedom of Information request to the tribunal service, asking how many other cases were going to be reheard due to similar circumstances. The answer was none. Chiles was the only litigant this had happened to and suffered further cost as a result.

Chiles' career earnings were highly volatile, including a lucrative period leading up to 2015, after which his earnings dramatically reduced. At this dip in his career, HMRC began their enquiry into his affairs and issued him with a devastating tax bill - a decision which has now been ruled to have been incorrect.

Given it took more than seven years and considerable expense before Chiles finally received justice, it is hardly surprising that Judge Cannan stated: "We do not underestimate the effect that the delay in determining the appeal must have had on Mr Chiles. There are significant amounts of tax and NICs at stake and the proceedings must have cast a shadow over his life for much longer than anyone would have wished."

“The judgment now confirms that - contrary to HMRC’s assessments - there was no underpayment of tax/NI,” says Chaplin. On the amount of tax in question, Chaplin adds, “The judgment contains numbers that were disputed. HMRC, as is their practice, didn’t allow for the substantial amount the tax/NI Chiles/BBL had already paid. Adding yet more uncertainty and expense, this would have required yet another hearing to resolve.”

The inequality of arms

The case for Basic Broadcasting Limited (the appellant) was argued by James Rivett QC, with Adam Tolley QC representing HMRC (the respondent).

Because of the broadness of the enquiry, looking at five different engagements, the hearing was unusually long for an IR35 case, lasting eight days in November 2019, followed by the additional two days in November 2021. Most cases are 2-3 days in total.

Chaplin says: "IR35 cases are notoriously complex, and it is not recommended for a litigant in person to try and fight their own corner, particularly when HMRC has a habit of hiring highly experienced Counsel for First-tier tribunal cases – which would traditionally just be represented by an HMRC inspector.

"With HMRC having access to the public purse to fund cases, this creates an inequality of arms, leaving the litigant with no option but to face enormous costs hiring similar firepower. Worse, HMRC has special arrangements with a chosen panel of barristers, where they pay considerably lower fees for similar skills.

"When it comes to IR35 cases, it's David v Goliath."

Key legal points of the case

The tribunal applied the IR35 statute and the tests to identify a contract of service based on the 1968 case of Ready Mixed Concrete (South East) Ltd v Minister of Pensions and National Insurance. This consists of examining whether personal service is present, along with sufficient mutuality of obligation and control, together with considering all of the other factors. After considering all of the circumstances, one must "stand back" and decide based on an impression of the overall whole.

Mr Chiles was undoubtedly providing his services personally, as it was him that his clients wanted to be on the television.

On mutuality of obligation, the tribunal relied on the authorities of HMRC v Professional Game Match Officials Limited [2021] EWCA Civ 1370 and Cotswold Developments Construction Ltd v Williams [2006] IRLR 181. Applying those cases, the tribunal considered that "In the circumstances, we are satisfied that the ITV Contracts involved mutuality of obligation, and the first stage of the test is satisfied for the ITV Contracts and the BBC Contracts."

On Control, Mr Rivett put forward an argument that where the parties agree in the contract what work is to be done, no relevant right of control can be identified from the fact that the worker can be required to do that work. He submitted that there is a logical and legal distinction between control exercised by both parties entering into the contract and control exercised under the contract.

The tribunal recognised that argument and accepted that "what is important is control exercisable as a result of the contractual relationship between the parties. In other words, the control must be derived from the contract, either the express terms or by implication. Further, we accept the broad proposition that the definition of the services to be provided may affect the extent to which there is control. If the services to be provided are defined in detail there may be less scope for the client to exercise control over what is done, where it is done, when it is done and how it is done. Much will depend on the nature of the services being provided and the context in which they are provided."

The tribunal also indicated that given the specific definition of the services, there was little scope for the broadcasters to control or direct what Mr Chiles could be required to do. However, once the tribunal examined the detail of the contractual provisions, they were satisfied that there was in both cases a sufficient framework of control to constitute Mr Chiles, prima facie, an employee of both the ITV and BBC pursuant to the hypothetical ITV Contracts. Crucially though, the level of this control was judged to be weak, with the tribunal noting: “we do not consider that the extent of the broadcasters' control in either case is a compelling factor."

The tribunal then considered that "the most significant factor that might displace the prima facie case that Mr Chiles was an employee under the hypothetical contracts is whether he was in business on his own account," and confirmed that "Mr Rivett's principal case was that Mr Chiles was in business on his own account and he submitted that the evidence in support of that case was overwhelming."

After a comprehensive examination of all the activities of BLL, the tribunal concluded that: "In all the circumstances we consider that Mr Chiles is to be treated as entering into the hypothetical contracts as part and parcel of that business. They were contracts for services and not contracts of employment."

The compelling evidence of being in business on own account

HMRC has powers beyond those of the police and can run an inquiry and form an opinion that tax is owed, which is binding in law. The taxpayer either has to pay up or appeal to a tax tribunal whereby they must discharge their burden of proof. This is a time consuming and costly exercise, as this case illustrated. Chiles had multiple engagements and called on five witnesses to provide oral evidence under cross-examination over a 10-day hearing.

Fortunately for Chiles, the preparation for his defence was outstanding, as can be seen by the plethora of facts presented to the tribunal to demonstrate that he was in business on his own account. The decision includes many such points, including:

- Hiring his own personal assistant.

- Paying an agency 15% of his fees to manage and develop his career.

- He was an entertainer and a "brand".

- He carried out unpaid activities to maintain and grow his profile whilst turning down a variety of work.

- He helped create a show and was entitled to a 50% share of production profits together with Avalon - a television production company, as well as the agency managing him.

- He developed and pitched his own ideas and contributed to other television programmes.

- He presented other programmes for multiple production companies.

- He wrote for several national newspapers.

- He had provided his services as a broadcaster and journalist to a significant number of clients. In the period 1996 to 2019 he contracted with nearly 100 different third parties.

- He was able to benefit from sound business management.

It is worth noting that HMRC were fully aware of all the above points, Chiles having submitted them on multiple occasions in the five years leading up to the first tribunal hearing. The question is why all this compelling evidence that demonstrated his innocence was seemingly ignored.

The tribunal also considered financial risk. For high profile freelance presenters, the industry can be harsh, as evidence provided by ITV indicated: "ITV were "quite good" at looking after their employees but brutally commercial in relation to freelance presenters”. The tribunal accepted Mr Chiles' evidence that he considered that he was "at risk" throughout his career once he left his employment at the BBC in 1996. His reputation and commercial value rose and fell. Every time he presented a programme his reputation and commercial value was at risk.

Chris Leslie, a specialist tax defence expert from Tax Networks, who successfully defended the IR35 case RALC Consulting, is surprised HMRC could ever have concluded that Chiles was a deemed employee.

"When you stand back and look at the whole picture," says Leslie, "It's evident that Adrian Chiles was in business on his own account. He presented and wrote, was involved in commercials and awards nights, and spoke at commercial conferences, all of which formed part of his business activities.

"He took risks, hired his own staff, and paid an agent 15% to help manage his profile and generate business. How HMRC considered him as an employee is perplexing."

Chaplin reiterates the point that HMRC has considerable powers and that with those powers should come responsibility. "In light of the clear mistakes made in this case by HMRC, questions need to be asked as to whether additional independent oversight is needed when HMRC inspectors are running complex status cases."

What happens next?

HMRC could seek to appeal the ruling, but the law doesn't allow them to merely “ try again" – they would need to either appeal based on perverse conclusions being drawn based on the findings of fact (a standard Edwards v Bairstow type challenge) or by claiming an error was made in the application of the law.

Chaplin thinks it highly unlikely, given the two sets of hearings, that HMRC have a route to claim the tribunal made any errors: "With regards to making errors in law, there seem no avenues open to them, as the ruling followed the standard approach in Ready Mix Concrete, without deviation, against the backdrop of a bucket load of carefully garnered and weighted facts."

But, Chaplin indicates more compelling reasons why HMRC should now leave Mr Chiles alone. Rule 2(1) of The Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Tax Chamber) Rules 2009 says that the overriding objective of the tribunal is to deal with cases fairly and justly.

Chaplin says: "They have put him through the wringer, both mentally and financially, due to the massive costs of having to defend himself over two hearings, despite always paying his taxes correctly and the Judge confirming that Chiles never set out to avoid tax at all.

"It would be wholly unfair for Chiles to expect to deal with the matter any further. He won fair and square, and HMRC should now leave him alone to recover from the ordeal he's been needlessly put through. The only thing left for HMRC to do is apologise to Adrian Chiles."